Armenian women have played an important role in the history of Armenia. Some of the most famous women in Armenian history include:

Queen Zabel I of Armenia ruled the Kingdom of Armenia from 1199 to 1252. She was the daughter of King Smbat III Bagratuni and Queen Dulandukht.

Queen Tamar Ruled the Kingdom of Georgia from 1184 to 1213. She was the daughter of King George III of Georgia and Queen Burdukhan.

Queen Catherine ruled the Kingdom of Georgia from 1465 to 1476. She was the daughter of King Constantine II of Georgia and Queen Ana.

Queen Ketevan ruled the Kingdom of Georgia from 1605 to 1624. She was the daughter of King David IV of Georgia and Queen Tamar.

Armenian Women’s role in Ancient Times

We know Hayk as the legendary forefather of Armenians, but what about the foremother of Armenians?

In ancient times we had Armenian queens who ruled over the country (Erato, Parandzem, Zapel).

The wives of kings also played a vital role in Armenian courts (they were called the Armenian Lady).

In the ethnic epic tale of “Daredevils of Sasun” Armenian female characters are described as conspicuous and courageous women who are independent in making their own choices in life.

From pagan times, Armenian women were considered to be the basis of the family according to some poetic fragments, legends, and historical evidence that have reached us today.

According to the Armenian historian Agatangeghos, in the pre-Christian period, the Armenian woman was considered a “mother spring,” “life-giver,” and “breath and life”.

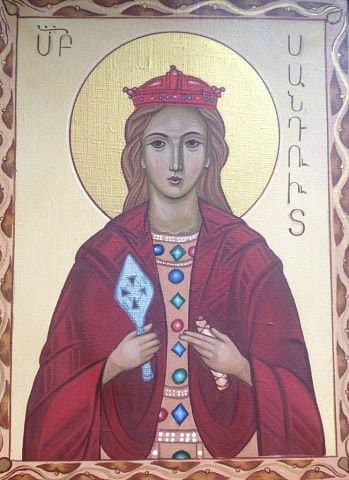

The Armenian ancient goddesses:

- Anahit

- Astghik

- Nane

played an important role in pagan mythology. Moreover, Anahit was one of the main goddesses, the daughter of Aramazd.

Earlier, Anahit was the goddess of war, indirectly proving that during the early period of slavery, Armenian women took part in military operations, perhaps in a non-secondary role.

Due to the development of public relations, the goddess Anahit was given a more feminine role becoming the goddess of fertility and childbirth.

Physical Traits and Characteristics of Armenian Women

According to a legend, Armenian eyes were blue like the waves of the Van Sea, deep as Armenian valleys, and charming like Armenia’s nature.

The first mention of the physical appearance of Armenians was made by Armenian historian Movses Khorenatsi, who described them as having curly, golden hair that reached to their shoulders, sunny-bright eyes, and curved nose.

However, historians noticed completely different factors based on the Artashesian coins. The facial features of the kings on the coins are almost identical to those of the modern people of Armenia.

It’s common for both genders to have a wide forehead, medium face size, long and curved nose, thick eyebrows, long and thick eyelashes, wide and mostly dark cute eyes, mostly thick and dark hair type, and white skin.

While the Armenian nose is considered a sign of an aquiline character for men, as high and proud as the mountains, the Armenian eyes are considered the most unique part of the Armenian woman’s body.

Usually, they are large and impressive, having a low position of the corners of the eyes that creates some universal sadness.

There is a popular concept among the locals on this – symbolizing the endless historical struggles, challenges, and difficulties that Armenian women faced through the centuries.

Armenians’ body features and psychological characteristics are strongly connected to the geographic mountainous position. They say those who live in the mountains have a stronger nervous system and are always ready to confront difficulties.

One of the features of Armenian women is a slim waist and wide thighs. The famous Armenian musician Sayat Nova metaphorically compared an Armenian woman to a tree- “long and thin spine just like the tree.”

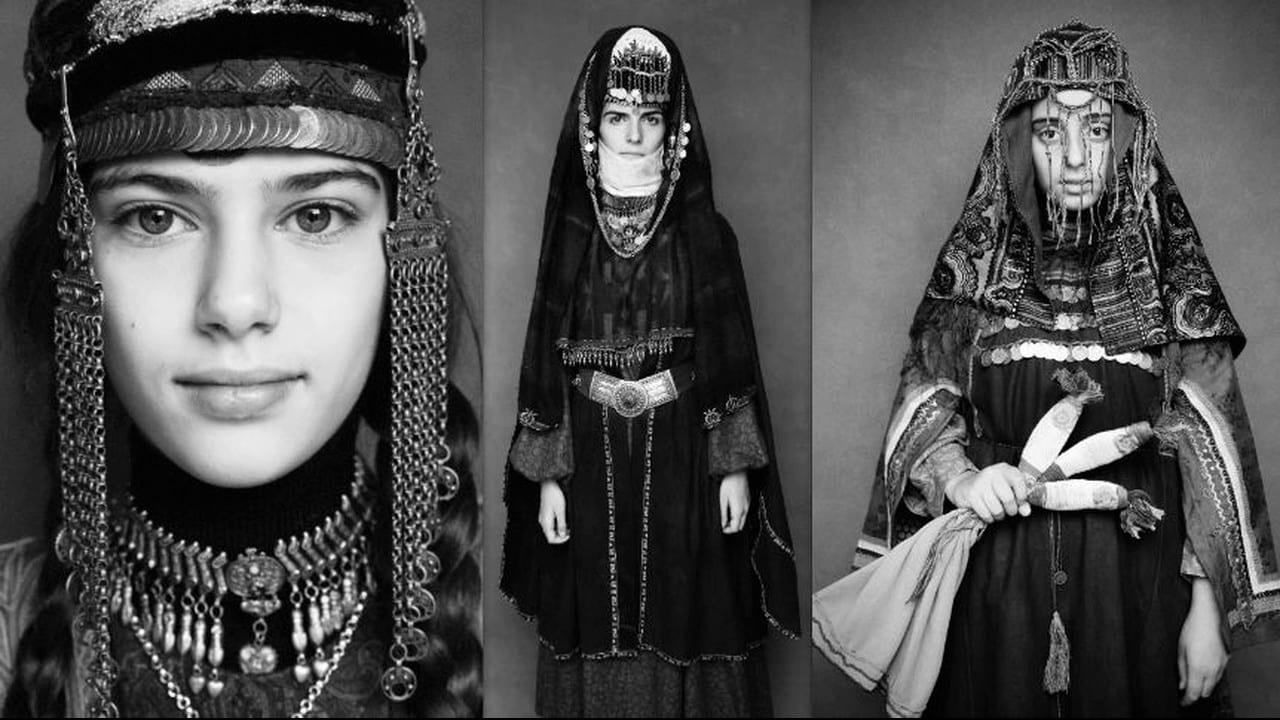

In old times Armenian women’s waist and beautiful posture were emphasized by Armenian traditional clothing called Taraz.

Women’s role in Armenian Traditional Family

In Armenian traditional families, women were responsible for the domestic sphere, including caring for children, cooking, and cleaning.

They were also responsible for spinning wool and weaving cloth. Women generally did not participate in public life; their primary role was maintaining the home and supporting their husbands.

In some families, women had more freedom and could participate in more public activities, but this was not the norm.

The division of gender groups in Armenia was specific to all people who lived in a pan-ethnic settlement, the manifestations of which have been preserved even until the XXI century.

The socio-economic, historical-political situation, customary law, and the church contributed to their preservation in the Armenian reality.

They were especially evident in the patriarchal setting, where the occupations were divided: outside work for men and inside work for women. The role of the patriarch of the family and his wife is especially emphasized, maintaining the strength of the family.

From childhood, an Armenian woman is brought up in the spirit of protecting family interests, fidelity, preservation of traditions, and obedience.

The Armenian women were described as:

- virtuous

- tolerant

- flexible

- kind

- secretive

- merciful

- humble

- purity, and this term was usually used in the context of sexual morality, that is, women should keep their virginity.

In almost all historical and ethnographic regions of Armenia, the patriarchal lifestyle of the family prevailed, which was characterized by a system of restrictions on women, especially brides. The restrictions on women were enforced early, becoming too strict after the wedding.

During the first year of marriage, the Armenian woman was not allowed to speak to anyone except her husband and children and was forbidden from leaving the house. There was even a sign language called Harsneren, “Language of the Bride,” created by the young Armenian brides.

This gesture-based sign language was used against the rule of silence on married Armenian women. In some parts, these restrictions still were on even after the birth of the first child and could last more than ten years.

Those restrictions were gradually diminishing when the woman became the mother of several children, especially when she appeared to be in the status of the head of the family-the speaker of the house, the patriarchal wife, giving her the priority of taking over the leadership of all the women in the family.

Most importantly, she was responsible for keeping the hearth fire of the house unquenched. She also set the following “prohibitions: do not spit on the fire, do not pour water, never put it out, etc.

Tonir – the hearth was considered sacred in Armenia. According to popular perception, the words family and home are synonymous; they are often used in the sense of the house, and smoke, sometimes a housewife.

The hearths were also the place of worship of the patriarchs. They served as protection for the living and symbolized the family’s wealth, longevity, healthy generation, and prosperity. The guarantor and maintainer of all these was the housewife.

Note that the housewife and other married women occupied a higher place in the Armenian patriarchal family than those in the Roman or Greek families. The patriarchal wife of the family was completely independent in housework.

Economically, she presented herself as a free person, and even in many cases, her husband turned to her for advice and often listened to her.

Women’s Rights in the History of Armenian Law

Before going back to the roots of the recognition of women’s rights, a turning point in the history of law should be mentioned.

The First Republic of Armenia (1918-1920) was one of the first countries to give women the right to vote and be elected in public institutions.

In the National Assembly of the First Republic, 8% of the deputies were women. In 1920, Diana Abgar was appointed Armenian Ambassador to Japan.

An unprecedented fact not only for the East but also for the West. Until now, only one case of a female ambassador was known in the history of world diplomacy (Rosica Schwimmer, who was Hungary’s ambassador to Switzerland).

After the appointment of Diana Abgar as Ambassador, Japan de facto recognized the Republic of Armenia, facilitating her humanitarian activities and assistance to refugees. She was also sponsored by the Armenians of Singapore and Indonesia.

Armenian women’s rights were recognized long before the First Republic of Armenia.

According to the Court Book (Datastanagirq) of Smbat Sparapet, the man is the head, and the woman is the legs, so the woman must obey the man.

This provision fully demonstrates the status of women in medieval Armenia and how issues were resolved between men and women. There were even some restrictions on women’s rights in the ministerial houses.

Nevertheless, since the 4th century, the equality of women’s and men’s rights was constantly emphasized in ancient Armenian legal documents. In the Middle Ages, Armenian law was based on ecclesiastical rules (related to the Christian church).

Equality between men and women was mentioned in the rules of Ashtishat (4th century), in the rules of Shahapivan (5th century), and in the “rules” of David Alavkaordi (12th century).

According to the rules of Shahapivan (444 AD), a woman must manage the family property in case her husband leaves her without grounds.

In addition, she can bring home a new husband. According to David Alavkaordi’s “Rules”, marriage is valid only in case of mutual consent of the bride and groom. “Marriage is not valid if it is based on violence.”

Finally, women’s rights were given proper consideration in secular (non-ecclesiastical) legal documents. The first references date back to the 5th century of King Vachagan’s Codex (a unique constitution).

However, they became more comprehensive and fundamental thanks to Mkhitar Gosh, who created the most influential Armenian Law Codex (12th century).

It describes the role of men and women in the family, as well as the ability of a woman to get an education. “Educated women are a treasure for society,” wrote Mkhitar Gosh.

His Codex stipulates that marriages should be managed by mutual consent and that if a husband failed to “make his wife happy,” then she had the right to divorce, in which case the property goes to the woman (dowry presented by her parents) and to leave the custody of the children to the father.

On the other hand, marriage required the parents’ consent, and a woman married without her father’s consent was considered a prostitute. In this sense, the rule of parental consent was simply contrary to the principle of voluntary marriage.

Also, there were parts dedicated to the recognition of women’s honor, respect, and dignity, women’s marital age, divorcing, remarrying, and other rights.

According to medieval documents, Armenian women were also entitled to own property, which they could donate, sell or bequeath without consulting with their husbands.

However, at the beginning of the 19th century, things took a turn for the worse. Armenian society’s social transformation under both the Russian and the Ottoman Empire totally turned Armenians into religious communities with only little prospects for women becoming not more than potential and actual mothers.

Social Activism and Education of Armenian Women

In the second half of the 19th century, a common saying appeared In Europe “Educating a boy – you educate a boy only, educating a girl – you educate the nation,” and Armenians were no exception. In the second half of the 19th century, many Armenian liberal intellectuals of that period played an important role in women’s education.

Initially, Armenian prominent writers (Perch Proshyan, Raffi, and many others) were actively involved in opening women’s schools in Tiflis, Shushi, and Agulis.

Armenian educational institutions such as the Hripsimyan school for women were established in Yerevan in 1850. Another school of the same name was founded in 1870 in Karin (Erzurum).

As a result, many Armenian women appeared to become cultural figures, scientists, writers, state, public and political figures, and practitioners of free crafts. Women’s schools were established in Eastern and Western Armenia.

Surprisingly, however, women’s social activism was more progressive under Ottoman rule, primarily in Constantinople. In this city, at the end of the 19th century, several Armenian women formed organizations with men and joined political parties. After graduating from women’s schools, many of them studied in Europe.

At that time, two of the most active women in Constantinople were Srbuhi Tusab (Vahanyan) and Zapel Asatur, who created the “Declaration of Women’s Rights.”

The provisions of the declaration were about equal rights for men and women, the right to choose a profession, and the abolition of double standards of morality, which were used by men in marriage.

The right to higher education as a means of improving a child’s upbringing, the right for women to equal participation in community activities, abolition of the custom of dowry, accepting the role of women in the preservation of the nation, and the transmission of its culture.

This declaration, in fact, carried the ideology of ensuring the financial independence of women. The emergence of this kind of declaration in Muslim Turkey was indeed revolutionary.

This illustrates that in the predominantly Muslim East, Armenians were the first to consciously raise the role of women in public life.

According to historical sources, any organization had not ratified the declaration. Still, many Armenian women had indeed started active economic and social activities, opening workshops, operating factories, and editing magazines.

In 1879 two most influential organizations, Patriotic Armenian Women’s Association and School-Loving Ladies’ Association (still functioning), were established in the Ottoman capital.

The thirst one was aimed at supporting women’s education. The second was actively engaged in training female teachers for women’s schools. Most students had financial waivers covering tuition fees and even accommodation.

Keeping all those institutions functioning was not an easy task under the Ottoman and Russian Empires to lead any expression of political or cultural activity.

Under Hamid, from time to time, educational institutions were closed to be reopened after the 1908 Young Turk coup. Meanwhile, under Russian authorities, Armenian schools for women had to be camouflaged as the so-called “vocational termed as centers.”

Religious Factors: Historical-Legal Point of View

Despite those progressive steps in terms of equality between women and men, ecclesiastical rules adopted by the church were stricter on women.

There were many rules about women who lost their virginity before marriage, their unjust slander, and the cases of cheating on women.

The death penalty was prescribed for girls who lost their virginity before marriage, and slanderous men were satisfied only with whipping.

In the relationship between a married woman and a man, all kinds of priority were given to the man; that legal status was based on the biblical “… you must obey your husband, he must rule over you”.

There is a whole context behind the Armenian wedding ritual: the priest asks the man, “are you the master” and the woman – “are you obedient.”

This suggests that a wife should be tolerant of her husband, which is not stated vice versa in most cases. So this meant women should tolerate any kind of injustice or violation of rights because certain problems in the family should not be available to the public.

The analysis of these medieval ecclesiastical rules shows that these rules have undergone a certain transformation and have been preserved in the traditional marital and social relations, which are more obvious in rural communities than in urban areas (not always).

Thus, a woman’s virginity, a father’s consent in a premarital relationship, a dowry provided by a woman’s family, and a man’s alleged decision-maker in family matters remain viable in rural communities, despite the influence of Soviet Armenia and Church bodies having no authority or role.

Armenian Women as Warriors

Armenian women actively participated in making the national history of the 20th century.

Educated women and wives of Armenian political figures became active missionaries of the national cause and even soldiers.

Many of the women took an active part in the armed Fedayis movement that began in Western Armenia in the 1890-the 1900s. They were fighting or helping soldiers in self-defense during the massacres under Sultan Abdul Hamid and in the Adana massacres.

Not rare were cases when Armenian women fighters fell victim to the genocide, though not just victims. Except for armed fights, they participated in humanitarian resistance and secretly distributed aid to the survivors.

In defense of Urfa (Edessa), Khanum Khatenjian headed 30 young women in fights. Many women fought along with men or even commanded many troops.

Armenian Women in Soviet Times & Modern Evolution

There is some activation of the role of women in Soviet Armenia, especially in public and economic life.

The Communist Party initially stated that it would not only ensure women’s equality but also cut women off from degrading domestic work. The Communist Party tried actively using women to destroy serfdom and bourgeois customs and traditions.

The practical application of this policy led to the fact that women in several professions formed the majority (doctors, teachers).

Soviet Armenia had 9000 women scientists in the 80s. The same number of women were doctors, 30 thousand teachers.

Some women held senior positions in large enterprises, especially in the food industry and trade. In other words, the economic role of women was intensified to better manage the female workforce.

Yet, the role of women in political life was only formal. There have never been women in the Communist Party elite.

On the eve of independence, the Supreme Council of Armenia of the first convocation in 1990, there were 260 deputies, 11 of them were women. In the Soviet era, there were several restrictions on women’s rights.

The moral code promoted by the Soviet leadership primarily restricted women. For example, during the Soviet era, beauty contests were never held in order not to tarnish the image of a “working woman.”

Based on modern perception, the aspirations of equality between men and women are given in Shahamir Shahamiryan’s “Ambush Glory” (1773). This is considered to be the first Armenian constitution.

“Every human being, be it a representative of an Armenian or another nation, be it a man or a woman, born in Armenia or abroad, must live in equality, be equal in their activities. “No one has the right to subjugate other people, and workers must be paid as they are normally paid for their activities.”

And finally, the introduction of the “National Constitution” of Constantinople (adopted in 1860 and ratified by the sultan in 1863) directly mentions numerous women’s rights to equal education with men, social security, and social and political activities.

If the first decades of Soviet rule clearly contributed to the growing involvement of women in various spheres of public life, then the manifestations of gender inequality have become a global issue in recent decades.

Armenian women have had their place in the political sphere for years. At present, the RA National Assembly has 31 deputy women.

However, the manifestations of gender inequality are still felt today, reflected in the rise of domestic violence and the limited involvement of women in political life and governing bodies.

In Armenia, as in many other countries, women still fight for equality, justice, and peace.