What kind of men are the Armenian Men

From a women’s perspective, Armenian men are mostly tall and handsome, with an oriental appearance. They are the most considerate, affectionate, tender… with heir black huge eyes, subtle humor, respect for family and women.

However, they are distinguished by a sharp change of mood, jealousy, unconditional love, loyalty to traditions, respect for family ties, and are hard-working. No one can control or re-educate an Armenian man, it makes no sense to conflict and fight with them. This is a fact. A woman can achieve her goals only by cunning.

To win the love of Armenian men, it is important to find out how to get their attention. There are no known facts that Armenian men prefer certain types of women. Therefore, there is no point in changing from a blonde to a brunette, losing or gaining weight. An Armenian man looks for mystery in a woman, or the presence of a twist that seems to be visible, but not solved.

He values his freedom so it wouldn’t work to impose oneself on him. Behaving as hard to get as possible, this will urge him to take further action, because Armenian men are essentially conquerors. Mysteriousness, inaccessibility and well-groomed appearance are the main weapons at the first stage to the goal.

Armenian men love those who Learn to cook their favorite dishes and learn the Armenian language, they will be flattered and it will be much easier to communicate when acquainted with their family and friends. And such acquaintances will certainly take place and will strengthen relationships and make them durable, as they need to please their parents. It is the opinion of the family that will play a decisive role in relationships. Whatever affection young men have, it’s breakable if the family so decides.

For a long-term relationship, he will certainly be proud of his partner for knowing his roots and all the extended members of his huge family.

They love to play the main role in their relationships, but wouldn’t love their partner to be deprived of their own opinion. This will cause them respect for you, and be proud that the independent partner recognizes them as the head of the relationship.

Do not try to check feelings of jealousy. Armenians, as a rule, are very jealous and a scandal can await, at worst a complete breakdown of relations.

Learn to respect Armenian men. Show them your mind, understanding, and admiration. Armenian men will be proud that they have such smart and understanding partners. And most importantly, if your relationships grow into a serious one and you have reached your initial goal, express your love for them. After all, every person needs to be loved.

Armenian Men and Education

Armenian men, as a rule, are well-educated, it is interesting to communicate with them, they look after themselves beautifully and take care. If you plan to start a family with them, then according to statistics the Armenians are good husbands, caring fathers, who put their families first. They respect their partners and their opinion. Parenting rests on the customs and traditions of their ancestors. From childhood, boys are instilled with the desire to grow up as a worthy respected person who knows how to take responsibility for their actions and for their future family. The Armenian fathers prepare their sons for life with love and patience and teach them how to work.

To get to know Armenian men more, read about how was Reddit Co-Founder Alexis Ohanian Thrilled For Armenians’ Approval of Fiance Serena Williams.

In the end, every man has his own principles and worldview and Armenian men differ too.

Domestic Violence Against Women in Armenia

There is an old folk saying in Armenia, “A woman is like wool, the more you beat her, the softer she will be.” Whether it is the result of a traditional mindset, rampant poverty, or simply a lack of knowledge, domestic violence has been a historically widespread and unacknowledged social issue in the Republic of Armenia.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Armenia was forced into a period of transition from a Communist state to an independent republic. This abrupt change proved to be an especially traumatic and violent one.

War with neighboring Azerbaijan, regional trade isolation, and a 6.9 magnitude earthquake that devastated the second largest city, were just a few of the catastrophes which further paralyzed an already struggling country. Furthermore, near-absolute economic collapse, due to rapid privatization, exerted considerable strains on the country’s population. This was reflected in significant emigration to Diasporan communities (Amnesty International, 2008). These harsh situations created an environment where women” the most vulnerable citizens of the country” were highly susceptible to violence.

Armenia, a traditionally patriarchal society, allows custom to dictate norms and practices, even in the 21st century. Armenian women are ideally meant to be chaste and passive. Custom says they are expected to marry the first man who asked for their hand and prove their virginity by showcasing a bloody sheet the morning after the wedding ceremony.

Tradition also dictates that men are providers of the family, while women are child bearers. Armenia’s unstable economy has resulted in unprecedented unemployment, creating a situation where men are unable to perform their roles as financial providers.

As a result, some men have adopted a widespread ritual of beating their wives. Vast unemployment pushes men towards alcoholism and gambling addictions, habits which encourage the ill-treatment of their wives. “Most” people attributed high levels of domestic violence to the devastating economic conditions in Armenia. International research indicates that women who live in poverty are more likely to experience violence than women of higher socioeconomic status (Minnesota Advocates for Human Rights, 2000, pg. 27).

Since traditional Armenian culture is intolerant of any discussion of issues pertaining to sexual rights of women, divorce or domestic violence, the crime is severely underreported and rarely prosecuted. The hush-hush culture of these taboo issues has truly led to a circumstance where countless women have fallen victim to the hands of abusive husbands, extended families and the government.

II. Background

In Armenia, there are no laws explicitly defining or prohibiting gender-based discrimination, a practice that is evident in numerous facets of society (Amnesty International, 2008). Although the battery itself is outlawed, women who attempt to report battery at the hands of abusive husbands are often faced with resistance from the police, the courts, their families and society in general.

The only legal options available to women are to either initiate a criminal action or to file for divorce (Minnesota Advocates for Human Rights, 2000, pg. 6). There are no legal alternatives for women who do not want to pursue criminal action but would like to protect themselves from future abuse. The government has not created restraining orders or other remedies to allow the husband to “cool off” while keeping the woman safe (Minnesota Advocates for Human Rights, 2000).

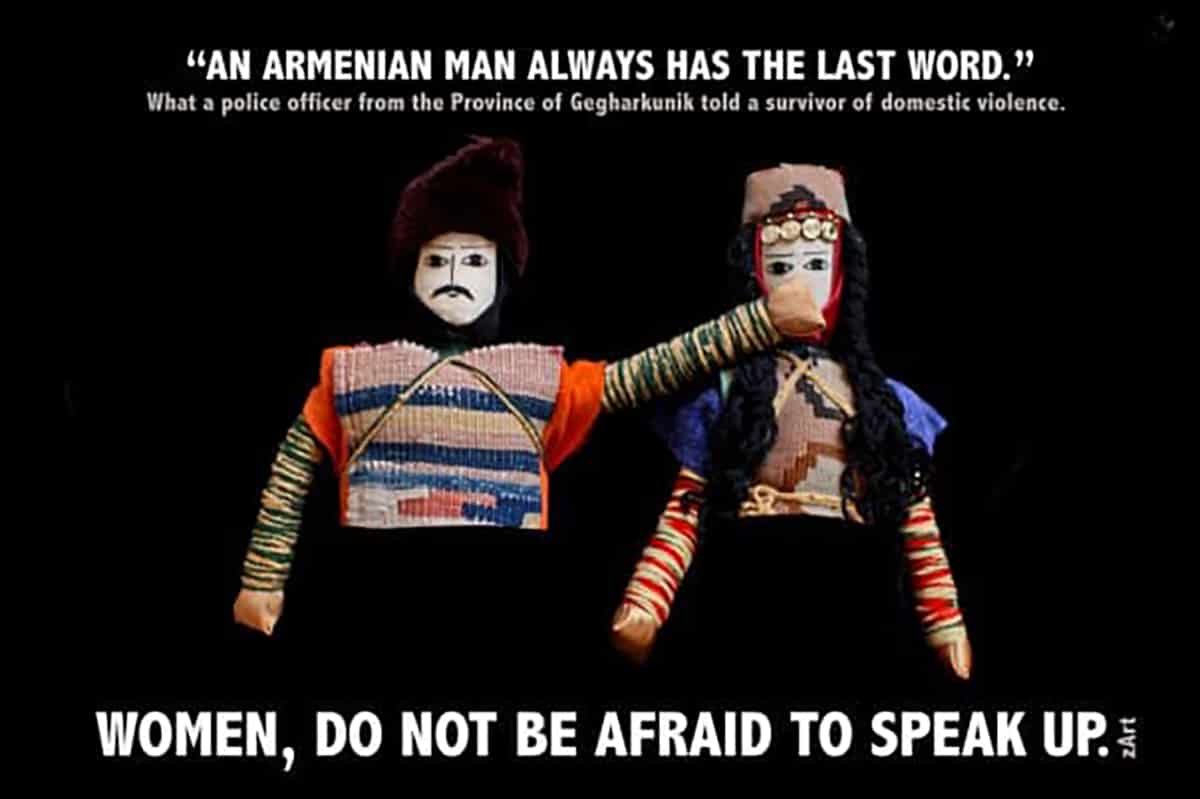

The pressure from society not to report cases of domestic violence plays a key role in ensuring the violence continues. “An Armenian man always has the last word,” a police officer from the Province of Gegharkunik told a survivor of domestic violence (Amnesty International, 2008). In an interview conducted by Minnesota Advocates, a mental health professional reported that he told a patient whose husband hit her that she was “too demanding and should remember that [she was] a woman and her husband needed love and warmth.” The same doctor stated that he advises other female patients to “accept men as they are and change [their own] attitude” (Minnesota Advocates for Human Rights, 2000, pg 26-27). These negative and discriminatory attitudes of medical and government officials keep women from seeking justice.

Domestic violence in Armenia, as in many other places, is often justified as something the wife did to upset her husband. In Armenia, the first question asked by police, prosecutors and judges to women sexually assaulted by their husbands is often “What did you do to encourage this?” (Amnesty International, 2008).

One woman who went to the police to press charges against her husband who threatened her with a knife and “kicked a glass door that broke over her, causing injuries,” was turned away by police who said it was a “family matter” (Minnesota Advocates for Human Rights, 2000).

Corruption can be identified as a significant problem in the Armenian legal system. Many officials including judges, police officers, and forensic doctors have been reported to take bribes to ensure favorable outcomes. Although official domestic legislation protects the rights of men and women equally in Armenia, there is a severe discrepancy between genders in the application of the laws. Women in Armenia face all forms of discrimination, from getting a job to domestic violence, and the legal system falls short of protecting their rights.

The violent treatment husbands subject their wives to is not limited to one type of abuse. “[Violence] takes the form of brute physical force, beatings, sexual torture (including being forced to engage in sexual activity against one’s will), authoritarian control (imprisoning the victim in the home, controlling contacts with others including family members, controlling all finances including access to food and clothing, etc.) and psychological abuse (constant degrading, insulting comments, threats, sadistic or controlling manipulation of the victims fears and vulnerabilities, “cat-and-mouse” toying with needs and expectations, threats against the children, etc.) (Theriault, 2009, pg. 4).

Many of these forms of abusive behaviour are unrecognized by Armenian officials and society in general. Psychological abuse remains nameless in Armenia, while the most visible form of domestic violence is significantly underreported, leading to sporadic statistical information. “In 2002, the World Health Organization, based on forty-eight surveys, concluded that a minimum of ten per cent and possibly as many as sixty-nine per cent of Armenian women have been physically assaulted by an intimate male partner at least once in their lives”

In many cases, women in Armenia suffer serious injury or even death at the hands of their husbands. “In a comprehensive study of murder committed in the home, a criminologist at Yerevan State University found that over thirty per cent of all murders between 1988 and 1998 were committed within the family. He also determined that eighty-one per cent of domestic murders were committed by men, and in thirty-five per cent of all cases the victims were wives or girlfriends” (Minnesota Advocates for Human Rights, 2000, pg. 2). In 1999, after brutally stabbing his wife to death in front of their two children, the husband stated, “I became suspicious of her unfaithfulness but had no proof. . . . Because of jealousy and drink, I beat her. . . .”

The man was charged with murder and sentenced to only nine years in prison (Minnesota Advocates for Human Rights, 2000).

Comedian Joey Medina talks about Armenian men.

III. Analysis

The interdependent family is a defining characteristic of Armenian identity. One of the major obstacles in battling issues of domestic violence in Armenia is the deeply rooted social attitude that sees violence against women as a “family matter”, not open for public discussion or judgment. Public discussion of the problem is regarded as an effort to destroy the family. “I put up with his beatings for 14 years because that’s what’s expected here in Armenia.

In the Armenian family, the woman has to put up with everything, she has to keep silent. The fact that I did something about it, that I went to the police and divorced my husband ” people in my village point at me and say she’s crazy, look at what she did to her husband, she should have kept quiet. It’s a stereotype, a national stereotype maybe, I don”t know, that if a woman goes to the police or the courts, she’s destroying the family”, confessed an Armenian woman during an interview (Amnesty International, 2008, pg. 26).

The government asserts that domestic violence is not an issue within the country. They do not want to acknowledge the topic because there is a strict mentality that precludes people from talking about their personal lives. In addition to the government’s inaction, the medical industry also views domestic violence as a private issue.

“By law, doctors are required to report suspicious injuries to the police including injuries resulting from domestic violence. Some members of the medical community nonetheless believe that domestic violence is a private matter and not one to be discussed with patients. Doctors from out-patient clinics and the ambulance service maintained that they do not report such injuries because they are “family problems” and doctors can do nothing about them” (Minnesota Advocates for Human Rights, 2000, pg. 19).

Due to strong social pressure on victims to preserve silence on domestic and sexual violence, there is a risk that these crimes and violations of women’s rights are both significantly under-reported and perpetrated with widespread impunity in Armenia. “[In a recent survey], eighty-eight per cent of respondents believed that domestic violence is best handled as a private matter rather than through the authorities. Only twenty-nine per cent of abused respondents sought help, in most cases from family members (Amnesty International, 2008, pg. 11). “In 1998, the Women’s Rights Center in [the capital city of] Yerevan surveyed one hundred women and found that forty-six had experienced some form of violence in the family, including sexual violence.

Of these women, only six had complained to legal authorities. In Gyumri, Armenia’s second-largest city, another women’s NGO surveyed one hundred married women from a variety of backgrounds; eighty admitted to experiencing domestic violence, and twenty of these said it happened often (Minnesota Advocates for Human Rights, 2000, pg. 12-13). Social attitudes in Armenia are accepting, and even vindicating of violence against women.

One of the most shocking findings is that these attitudes are not restricted to men; they are widespread among women themselves. Many women believe that abuse is a normal part of marriage and are unconvinced that a life without it can exist. Since women are expected to move into their husband’s household with their husband’s family, mothers-in-law play a major role in the abuse of the new bride. “More detailed quantitative data was published in 2007 in the form of a survey of one thousand six women, conducted for the Women’s Rights Centre NGO by the Turpanjian Center for Policy Analysis within the American University of Armenia.

Across the cases of physical abuse, in eighty-five per cent of cases husbands were the perpetrator, and in ten per cent of cases, mothers-in-law” (Amnesty International, 2008, pg. 11). Fathers-in-law also living in the same household have proven to be physically violent towards their son’s wife. “There were arguments with my father-in-law and sister-in-law. We lived in the same house. She wanted to divide up the flat so that she and her son would have one of the rooms.

They started picking fights with me and it got to the point where my father-in-law hit me around the head with a glass ashtray”, reported a woman during an interview (Amnesty International, 2008, pg. 16). One woman’s father-in-law told her, “You think that’s a beating? When I beat my wife, that was a beating” (Minnesota Advocates for Human Rights, 2000). Behind public support for the family, unit lays an institutionalized culture of preserving silence on the violence that occurs within the family and denying justice to its victims.

In Armenia, the social disgrace associated with divorce is exponentially worse than that associated with domestic violence. If a woman files for a divorce, she will be considered the shameful destroyer of her family’s dignity. A police representative stated that women should be ashamed to report cases of domestic violence because such reporting could lead to divorce (Minnesota Advocates for Human Rights, 2000, pg 22). The importance of escaping social disgrace was reflected in the fact that “eighty-eight percent of respondents to the Women’s Rights Centre survey believed that domestic violence is best resolved within the family and not taken to the police” (Amnesty International, 2008, pg. 25).

The Armenian government explains that a disproportionately high number of women are unemployed because traditionally, women are more oriented towards family and children. This traditional female role of housewife and mother has turned women into “household slaves”. “Their housework has increased enormously, while their inability to contribute cash to the family economy has reduced their authority and independence in the family. Thus, the economic situation has increased women’s dependency on men” (Minnesota Advocates for Human Rights, 2000, pg 12).

Another important reason as to why violence against women continues to prevail in Armenia is because women are unaware of the meanings of domestic violence and are uneducated about their rights to protection from it. According to a study conducted by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) in 2007, many women admitted that they were unaware of their rights and were without access to information (OSCE, 2007). The problem is rooted in the fact that many Armenian women are unable to define domestic violence and abuse as general concepts. Most women, for example, believe that domestic violence consists only of physical abuse, rather than including psychological and economic mistreatment. These distorted perceptions further contribute to non-reporting and under-reporting of domestic violence.

In light of the fact that women often do not have the option to pursue criminal charges against their abusive husbands, the only other option available to try and escape violence is divorce. As previously mentioned, divorce is highly stigmatized and can often carry heavier consequences as staying in an abusive relationship. Even when seeking a divorce, women are sceptical of what justifies breaking up the family.

In one case, a woman questioned whether the fact that her father-in-law and brother-in-law forced her to have sex with them and prohibited her from leaving the house was reason enough for a divorce (Minnesota Advocates for Human Rights, 2000). Although divorce is one of the few remedies utilized by abused women, it does not always solve the problem. At times, men who are angrier following a divorce find and continue to beat their ex-wives. “An NGO staff member recounted a story of a woman who was beaten by her ex-husband every week when she picked up her child from visitation” (Minnesota Advocates for Human Rights, 2000, pg. 41).

10 Handsome Armenian men

IV. Summary

Two primary factors contribute to the unique dynamic of domestic violence against women in Armenia. First is the silent attitude surrounding the issue, and second is the fact that violence often takes place within the broader context of the family (Amnesty International, 2008). Tradition is what allows for these two dynamics to continue prevailing. “Cultural traditions and norms, stereotypes and expectations of gender roles have placed societal pressures on women and their role in all aspects of society. This is a trend that is very apparent in [Armenia].

Gender issues here, as in most transitioning countries, can be viewed as part of a broader issue of values or value-systems”. In the overriding majority of transition countries or newly independent states, promoting and calling for gender equality was and is viewed as something imposed by international aid agencies which will destroy culture, traditions and the classical view of the family” (Titizian, 2010, pg. 2).

There have been recent efforts on behalf of NGOs to battle the issue of domestic violence in Armenia, but even with the collective efforts, they are met with much resistance. Armenian officials have been particularly resistant to the campaigns working to end violence against women. These NGOs have been struggling simply to get the issue of domestic violence mentioned in newspapers, television and other media outlets (Johnson, 2007).

A campaign entitled, “16 Days of Activism against Gender Violence” aiming to increase public awareness on gender-based violence was launched last year in Yerevan. The “16 Days of Activism against Gender Violence” was an international campaign from November 25, the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, to December 10, International Human Rights Day and symbolically linked gender violence and human rights issues. Other efforts include new shelters available to women. Since 2002, a handful of shelters have been operating in Armenia, despite facing much criticism for making domestic violence a public issue. “These shelters, which are run by non-governmental organizations, are reliant on intermittent funding”.

Unfortunately, most have had to close down due to a lack of funding (Amnesty International, 2008, pg. 2). There is also a draft law being discussed, which will finally criminalize domestic violence. Furthermore, police training programs have been initiated to implement proper responding techniques for domestic violence cases.

An important step towards progression is for both the Armenian state and society to first and foremost acknowledge that this problem exists. Public awareness and educational measures must be enforced to emphasize that violence against women is not a private issue, as tradition may like to see it, but a violation of women’s basic human rights.

Fundamental human rights and dignity must become priorities in all social relations. The concept of sacrificing freedom, safety, and justice for the preservation of family and ego must no longer be the norm. Detestable practices, which subvert human rights and risk the wellbeing of individual members of the family, need to be done away with if women of Armenia are going to become equals with men. Respect for women should become just as much a part of the culture as deep family values.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in 2019, and has been completely revamped and updated for accuracy and comprehensiveness.