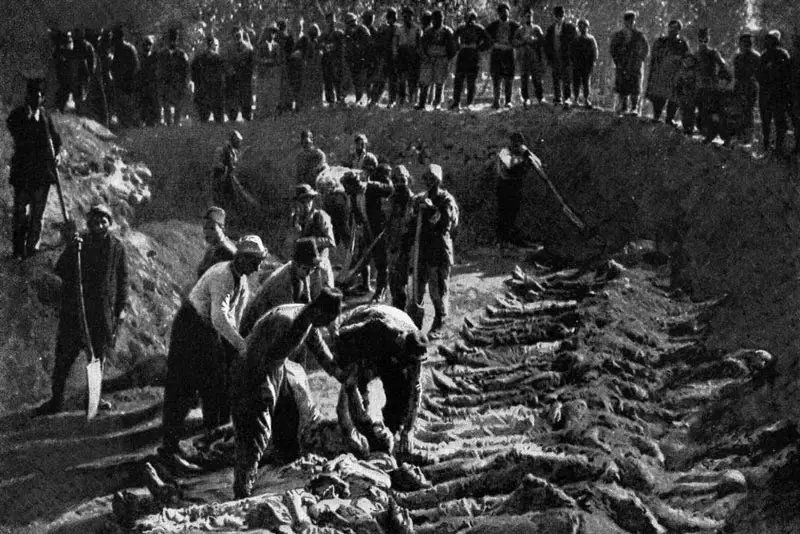

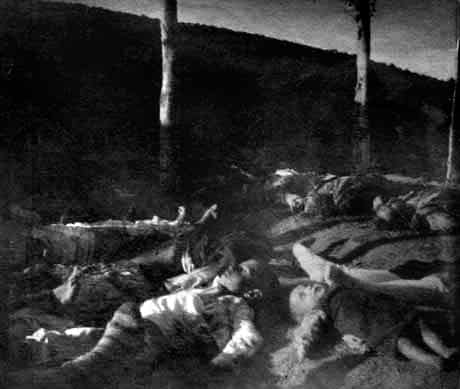

The Hamidian massacres also referred to as the Armenian Massacres of 1894–1896, and Great Massacres, refer to massacres of Armenians of the Ottoman Empire in the mid-1890s, with estimates of the dead ranging between 80,000 to 300,000 and at least 50,000 children made orphans as a result.

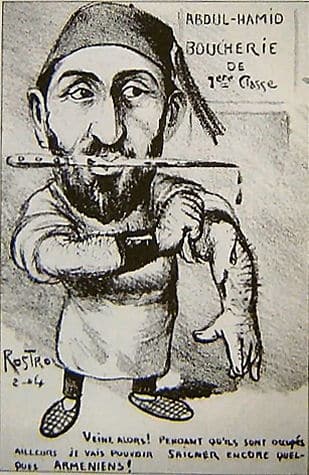

The massacres are named after Sultan Abdul Hamid II, who reasserted Pan-Islamism as a state ideology in his efforts to reinforce the territorial integrity of the embattled Ottoman Empire. Although the massacres were aimed mainly at the Armenians, they turned into indiscriminate anti-Christian pogroms in some cases, such as in Diyarbekir, where some 25,000 Assyrians were killed (see also Assyrian Genocide).

When did the Hamidian massacres start?

The massacres began with incidents in the Ottoman interior in 1894, gained full force in the years 1894–96, and tapered off in 1897, as international condemnation brought pressure to bear on Abdul Hamid.

Even though the Ottomans had previously suppressed other revolts, the harshest measures were directed against the Armenian community.

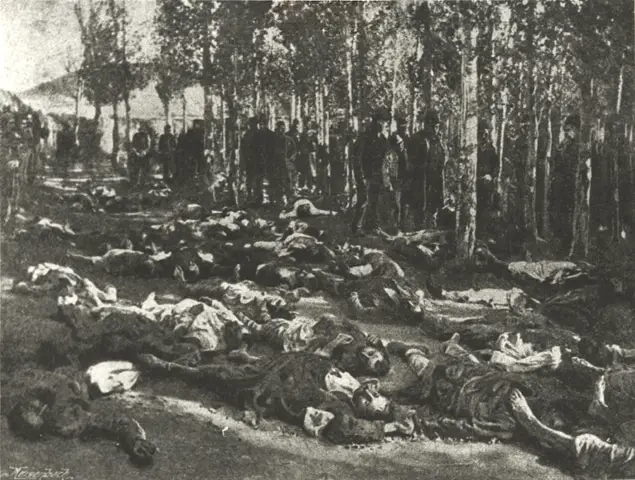

They observed no distinction between age or gender and massacred them with brutal force. This occurred at a time when the telegraph could spread the news around the world, and the massacres were extensively covered in the media in Western Europe and the United States.

Where did the massacres take place?

Massacres of Diyarbakir were massacres that took place in the Diyarbekir Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire between the years 1894-1896.

Who were the targets?

The events were part of the Hamidian massacres, which targeted the region’s Christian population: Armenians and Assyrians.

The massacres initially targeted the Armenians, instigated by Ottoman politicians and clerics under the pretext of their desire to dismantle the state. Still, they soon changed to general anti-Christian pogroms as they moved to the Diyarbekir Vilayet and surrounding areas of Tur Abdin, which was inhabited by Assyrian/Syriac Christians. Contemporary accounts put the total number of Assyrians killed between 1894-1896 at around 25,000.

Who led the attacks?

Kurdish raids on villages in the Diyarbekir Vilayet intensified in the years following a famine that ravaged the region. This was followed by fierce battles between Kurds and Shammar Arabs. In August 1888, Kurdish Aghas led attacks on Assyrian villages in Tur Abdin, killing 18. Requests for an investigation by Patriarch Ignatius Peter IV went unanswered by the Porte.

Another Kurdish raid in October 1889 targeted several Assyrian/Syriac villages, during which 40 villagers, including women and children, were killed. These events were the first signs of the massacres that would characterize the Diyarbekir Vilayet for the following decade.

The Hamidian massacres came when some 4,000 Armenians in the Sasun district of Bitlis Vilayet in 1894 rebelled against Kurdish nomadic tribes, who demanded traditional taxes from them. Local authorities reported this to the Sultan as a major revolt. The Sultan responded by sending the Ottoman army supported by the Hamidiye cavalry and local Kurdish tribes.

How did the massacres start?

After clashing with the Armenian rebels, the Kurds descended upon Armenian villages in the regions of Sasun (Sassoun) and Talori, between Muş and Silvan, massacring its inhabitants and burning several Christian villages. More than 7,500 Armenians died as a result, and intervention by European powers led to the dismissal of the Governor of Bitlis, Bahri Paşa, in January 1895.

Foreign powers’ contributions for solutions

Three European Powers – Britain, France, and Russia – thinking that reform of the Ottoman local government would help to prevent violence as occurred in Sasun, proposed to Sultan Abdul Hamid II a reform plan, planning control of the Kurds and the employment of Christian assistant-governors.

The Sultan was unwilling to yield to the desires of the Powers. During the Spring and Summer of 1895, months of unfruitful negotiations passed.

After a demonstration in Constantinople on September 30, 1895, organized by the Armenian Hunchakian Party to ask for speedy enactment of the reforms, Christian neighborhoods in the city were attacked by angry Muslim mobs, and the city descended into chaos.

The massacre in Constantinople was followed by more Muslim-Armenian conflict in other areas, usually costing the lives of much more Christians than Muslims. Western pressure on the Sultan increased, and he eventually gave up on their demands. A Firman of the reforms was issued in October 1895.

In retrospect, the announcement of the reforms only further exited the already heated atmosphere in the Ottoman Empire. As news of clashes and massacres spread throughout the empire, Diyarbekir took its share, with Muslim-Christian distrust reaching unprecedented levels.

How religious it was?

Generally, Muslims had a distorted view of what the European-inspired reforms would mean. Muslims, also in Diyarbekir, thought that the Armenian Kingdom was about to be created under European powers’ protection and that the end of Islamic rule was imminent.

Muslim civilians bought large amounts of weapons and ammunition. The influential Kurdish Sheikh of Zilan, who played an important role in the massacres of Armenians in Sasun and Mush in the previous year, was present in the city inciting the Muslims against Christians.

It was rumored that Kurdish tribal leaders outside the town had promised to send 10,000 Kurdish fighters to avenge themselves. Muslim notables in Diyarbekir, who had lost their trust in the Sultan, telegraphed him that: Armenia was conquered with blood. It will only be yielded with blood.

The massacres began in the city of Diyarbekir itself after unidentified individuals fired shots outside the Grand Mosque («Ulu Cami») in the city center during the midday Muslim Prayer of Nov. 1, 1895. Muslims attacked Armenians in the surroundings, and soon, the violence turned against Christians without exception and spread over the whole of the city.

They then started the looting, which was joined by common civilians and government officials alike. The entire market was set on fire. The financial losses of this day were estimated at two million Turkish Pounds.

How the attacks were orchestrated?

Attack on Christian neighborhoods systematically began the next morning: houses were looted and burned, men, women, and children killed, and girls were kidnapped and converted to Islam.

The French vice-consul writes that the authorities had to close the city’s gates «fearing the coming of Kurdish tribes on the outskirts of the city, which do not differentiate between Muslims and Christians in their raids.»

Some Christians could protect themselves with the few weapons they had owned in narrow streets, which were defendable. More than 3,000 Christians of all denominations gathered at the monastery of the Capuchin Fathers in the city, and about 1,500 were protected by the French Consulate.

Diyarbakir massacres ended after three days, likely at order from the governor. The number of deaths within the city exceeded 1,000, most of whom were Armenians, and 1,000 were missing. A similar number of deaths occurred in the surrounding villages.

How did converting to Islam Saved Lives?

Many Christians survived the killings by converting to Islam at gunpoint. According to some accounts, some 25,000 Armenians only turned to Islam during the massacres. Many of them returned to Christianity after the end of the period of persecution and returned to their villages once again.

William Ainger Wigram visited the region a few years later and witnessed the scenes of destruction. According to him, the Assyrians of the city of Diyarbekir suffered less than their Armenian co-religionists, whose quarter was still completely demolished. He also observed high anti-Christian sentiments among the city’s Muslims.

There are few indications that Armenians had a role in «provoking» the conflict, as is claimed by some Ottoman sources, by attacking mosques. Clearly, however, protests of Christians against the new Governor, Eniş Paşa, in September 1895 were an important factor in further souring Muslim opinion.

The massacre in Diyarbekir city was one of the most violent and bloody massacres in the period, extensively reported on by the French Consul in the city, Gustave Meyrier.

How Many Survived in Different Villages?

Massacres in the countryside lasted for 46 days after the initial massacre of Diyarbakir. In the village of Sa’diye, inhabited by 3000 Armenians and Assyrians, the Kurds first killed men, women, and finally children. A group of them found shelter in a church, but the Kurds managed to burn it and kill the refugees. Only three made it alive by hiding between the corpses.

In Mayafaraqin (Silvan, Farkin), a town of 3,000 of mixed Armenian, Jacobite, and Protestants, only 15 survived the killings. The rest were killed like what happened to Sa’diye.

The Assyrian village of Qarabash was destroyed, and Qatarball only 4 survived of 300 families. Most of the villagers died after burning the church in which they gathered. Isaac Armalet, a contemporary Syriac Catholic priest, counts 10 more villages that were entirely erased from the map, accounting for a total of 4,000 victims.

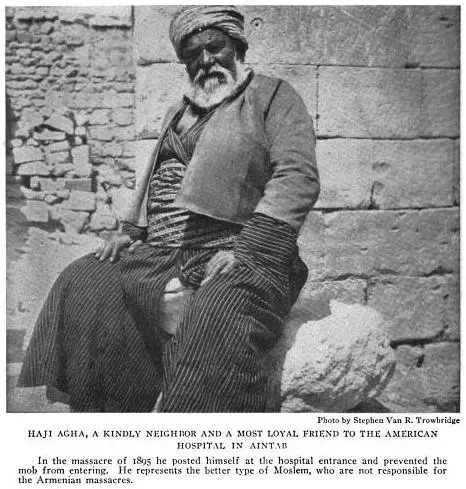

Mardin, the largest city and the capital of the subprovince (sancak) of Mardin, was spared the massacres inflicted on other sancak’s in Diyarbakir. Many of its Muslim notables were anxious to protect their own interests and wanted to maintain the tolerant image of the city.

The city was also characterized by the fact that the neighborhoods of Muslims and Christians were intermingled, making it difficult to distinguish between them. The Muslims knew that the entry of outside forces would lead to an indiscriminate massacre of its inhabitants.

The first Kurds entered the city on 9 November, coming from the village of Ain Sinja, which they destroyed. A local Muslim force confronted them and drove them back. The Governor then arranged the city’s defenses and distributed weapons among its Christian population as well.

Two subsequent attempts from the Kurds to break into the city also failed. At the end of November, the governor of Diyarbakir issued the order to protect the churches, although the atmosphere remained tense until spring 1896.

Despite the protection of the Christians of Mardin, the neighboring villages in Tur Abdin faced a different fate. The village of Tell Armen was completely sacked and burned and its church partially destroyed.

al-Kulye, made up of about 2,000 Jacobite individuals, was also destroyed and burned down, killing about 50 of its inhabitants. Banabil was also attacked and destroyed. At the same time, al-Mansurye survived after receiving support from nearby villages.

The village of Qalaat Mara, The Jacobite Patriarchal seat, was abandoned after the Kurds attacked it. Its residents sought refuge at the Saffron Monastery, where they arranged their defenses and were able to hold the attacks of the Kurds for five days.

Father Armalet cites two different versions of the role of the Ottoman army: In the first one, the army aided the Kurds in attacking the monastery, killing 70 Assyrians. The governor then sent 30 soldiers who accompanied the besieged to their villages and provided them with protection.

In the second version, which agrees with the official story, the Kurds attacked the monastery independently. The Mutasarrif sent a force that ordered the Kurds to withdraw. Upon their rejection, the Ottomans attacked them and killed 80 men.

Historians agree that the town of Jezireh, east of Tur Abdin, stayed calm and secure during the massacres. However, villages around Midyat were not spared from destruction and murder. and tells the monk Dominican monk father Gallant witnessed scenes of destruction as he passed in these areas in 1896.

How many Christians live in Diyarbakir?

The Assyrian population of the Sanjak of Mardin declined sharply after the massacres. In an estimate before the First World War, Christians formed roughly two-fifths of its population of 200,000. Tur Abdin ceased to be a «Christian island» as it counted about 50% of its population of 45,000.