The assassination of Talaat Pasha was part of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation’s Operation Nemesis. In 1919, in Yerevan, the general assembly of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation party enacted a resolution calling for the implementation of the verdicts it had reached.

Soghomon Tehlirian executed the death sentence on Turkey’s Minister Talaat on March 15, 1921, in Berlin. Tehlirian is considered a national hero in Armenia.

The target turned out to be Talaat Pasha, the erstwhile Interior Minister of the Ottoman Empire and a key member of the ruling wartime triumvirate of the nationalist Committee of Union and Progress party. His assassin was a young Armenian named Soghomon Tehlirian.

Soghomon Tehlirian – Operation Nemesis

A survivor of the Armenian Genocide, Soghomon Tehlirian assassinated the former Ottoman Interior Minister Talaat Pasha in Berlin as an act of retribution for Talaat’s role in organizing the Armenian Genocide during World War I.

In the 1920s, widespread revenge killings for the 1915 Armenian Genocide took place, and the world turned a blind eye to it.

The assassination occurred in broad daylight and led to Tehlirian’s arrest by the German police. After a two-day trial, Tehlirian was found not guilty by a German court and was set free.

Soghomon Tehlirian, Operation Nemesis: Motive

In June 1915, the Ottoman police ordered the deportation of all the Armenians in Erzinjan, where Tehlirian’s family lived. They were deported and then massacred along with other Armenians.

He was motivated by a desire to avenge the brutal killings of his family members. Soghomon Tehlirian joined Operation Nemesis in 1921, a covert assassination program targeting those responsible for the Armenian Genocide.

Details of Operation Nemesis

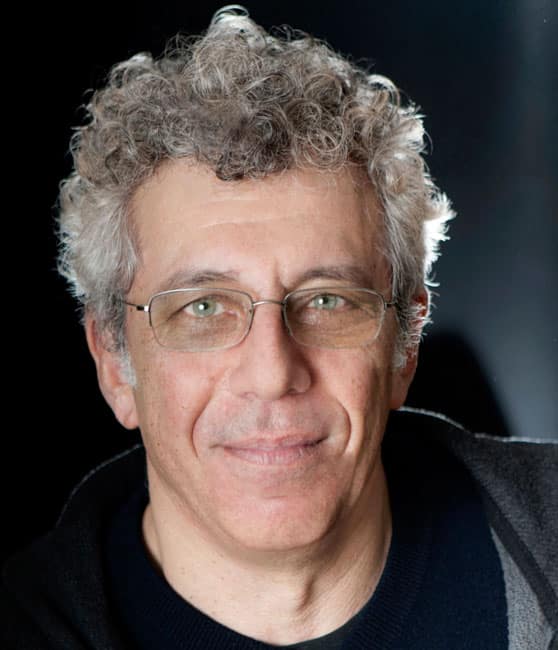

Soghomon Tehlirian (Tehlerian) (1897-1960). He was a 23-year-old student who had survived the Armenian Genocide in Erzinga and was selected to execute the mission.

Some of Berlin’s Armenian diplomatic mission personnel gave logistic support, and other A.R.F. members worked from outside. Once Talaat’s whereabouts were established, Tehlirian arrived in the German capital in December 1920.

He carried out a surveillance task with his associates for the next three months. He rented an apartment near the Turkish leader’s house to study his everyday movements.

Talaat was killed by Tehlirian with a single shot on March 15, 1921, as he came out of his house in the Charlottenburg district. The assassination occurred in broad daylight and led to Tehlirian’s immediate arrest by German police.

The trial of Soghomon tehlirian

At his subsequent trial, lawyers, psychiatric experts, police officers, and jurors tried to get their heads around what had prompted his crime. They knew that something terrible had happened to the Armenians during the recent war in Anatolia.

Tehlirian was a polite and musically-minded young man who made a good impression on a string of landladies. In court, he described the killing of his family and his own survival. He said that his mother’s appearance to him in visions had driven him to his act of revenge.

Johannes Lepsius, the German expert on the Armenian question, gave the court a potted summary of what had transpired in wartime Anatolia. Still, the most gripping testimony came from an unknown Armenian cleric who had traveled from Manchester to testify on Tehlirian’s behalf.

He was Bishop Grigoris Balakian, one of several witnesses called by the defense. In what was perhaps the high point of the trial, he outlined the gripping story of his own deportation and survival in rusty but effective German.

Acquittal of Soghomon Tehlirian

Tehlirian was acquitted of murder, somewhat sensationally, and lived another four decades until he died in San Francisco in 1960. After the trial ended, conspiracy theories about its outcome flourished.

Many people believed that Tehlirian was by no means as confused or as innocent as he had made out; that he had, in fact, been working variously for British or Russian intelligence or carrying out orders as part of a campaign by Armenian revolutionaries to target those they held responsible for the wartime extermination.

Soghomon Tehlirian marries Anahit Tatikian

The world’s amnesia about the ‘great catastrophe’ was beginning. Tehlirian changed his name and married Anahid. They settled in Valjevo, Serbia, where Tehlirian practiced his marksmanship at the town’s gun club.

He had found a kind of resolution’ but not peace. After 1945, Turkish agents tracked him down. He moved to Morocco, and then to San Francisco.

Real Video Documentary of Nemesis’ Soghomon Tehlirian’s Trial

Books on Operation Nemesis

Operation Nemesis was how the Armenian survivors of the Genocide reacted to injustice. The world was trying to open a new page in history after World War I, each nation trying to lick its own wounds to heal with no intentions to open new frontiers.

The first and short-lived Armenian Republic, 1918-1920, didn’t get the chance to officially sue the Perpetrators of the Genocide as the Ottoman Empire was no more. They chose to take justice into their own hands, and when Soviet Armenia was formed Armenians were forced to let go and not to speak of.

The only Records of this important part of history are in the memoirs of Soghomon Tehlirian and Bishop Grigoris Balakian, one of the witnesses of Soghomon’s Trial.

Soghomon Tehlirian’s book: Memoirs, Talat’s Terror.

This collection of Tehlirian’s memoirs describes the events between 1915 and the assassination of Talaat Pasha and the subsequent trial, in January 1921 in Berlin.

The trial, which resulted in Tehlirian being found not guilty, served as another reminder for the European public about an unprecedented crime against humanity: the Armenian Genocide committed by Turkey.

The book was printed in 1953 in Cairo, and in 1993 in Armenia, on both occasions under the title Recollections, The Terror of Talaat. The memoirs were written down and edited by the writer, social activist, and statesman Vahan Minakhoryan.

The importance of Tehlirian’s book for the Armenian people is unquestionable, and it will undoubtedly be of great interest to readers outside Armenia.

A work of great social and historical significance, the collection is now accessible to English-speaking readers, more than 60 years after the memoirs were first published.

Armenian Golgotha: A Memoir of the Armenian Genocide, 1915-1918.

Balakian slipped back into diasporic obscurity, returning to his pastoral duties in Lancashire before becoming bishop of the Armenian Apostolic Church in southern France, where he died in 1934.

A much-expanded version of the story that he related at Tehlirian’s trial was published in Armenian the year after the trial.

But few, outside the Armenian community, knew about this remarkable wartime memoir, which Balakian had begun writing virtually as soon as he had managed to return home to Constantinople disguised as a German soldier in the late autumn of 1918.

Now it is at last available in English, in a fluent and readable rendering, and it takes its place as one of the key first-hand sources for understanding the Armenian genocide.

Fueled by the anger of the survivor, the strategic vision of a spiritual leader, and the intellectual’s desire to understand, Armenian Golgotha provides a more gripping and harrowing account of the tragedy than any I have read. It is a powerful and important book.

Bishop Gregoris Balakian- Biography and Deportation account

Born in the Anatolian town of Tokat in 1876, Balakian had studied engineering for a year in Germany before becoming a priest, working on diplomatic missions for the Armenian Patriarch in Istanbul.

When World War I broke out, he was in Berlin studying theology but returned to the imperial capital a few weeks later because he wanted to witness what he believed would be the collapse of the Ottoman regime.

Instead, the following April, he was arrested in a round-up of Armenian notables. This decapitation of the capital’s Armenian intellectual, commercial, and political leadership marked the onset of a campaign of systematic murder.

Through the spring, summer, and autumn of 1915, while Balakian himself suffered the uncertainties of internal exile in the small central Anatolian town of Chankiri, a campaign of despoliation, deportation, and massacre unfolded.

In May a new law was passed in Constantinople permitting Armenians to be forcibly deported. The following September an expropriation law regularized the seizure of their property. In the intervening months, hundreds of thousands of people were made to leave their homes.

They were either killed or allowed to starve on forced marches across Anatolia toward the Syrian desert town of Der Zor in the south. Estimates of the eventual death toll, which are necessarily imprecise, range from 800,000 to 1.5 million people.

Tehlirian was tried for murder but was eventually acquitted by the German court. The trial of Tehlirian was a rather sensationalized event at the time, with Tehlirian being defended by three attorneys, including Dr. Theodor Niemeyer, Professor of Law at Kiel University.

The trial examined not only Tehlirian’s actions but also Tehlirian’s conviction that Talaat Pasha was the main author of the Armenian Genocide. The defense attorneys made no attempt to deny the fact that Tehlirian had killed a man, and instead focused on the influence of the Armenian Genocide on Tehlirian’s mental state.

When asked by the judge if he felt any sort of guilt, Tehlirian remarked, “I do not consider myself guilty because my conscience is clear … I have killed a man. But I am not a murderer.” It took the jury slightly over an hour to render a verdict of “not guilty”.

The “not guilty” verdict of the jury was based on the account of Tehlirian’s experience during the Genocide. After the trial, Tehlirian moved to the former Yugoslavia where he lived for nearly thirty years. After the end of World War Two, he and his family fled to Casablanca.

In 1956 Tehlirian moved to the United States. He died in 1960 in San Francisco. The Armenian Genocide and the 1921 trial of Soghomon Tehlirian set precedents for the 20th century.

“For the first time in legal history,” a German-born American lawyer Robert Kempner wrote in 1980 in retrospect, the Berlin court recognized the principle (if not de jure, then at least through the trial’s overall course and impact on the outside world)…

“… that gross violations of human rights, and especially genocide that is committed by a government can be contested by foreign states, and that does not constitute impermissible meddling in the internal affairs of another state.”

Soghomon Tehlirian Square in France

A square in the French city of Marseille is officially named after Soghomon Tehlirian—the Armenian who assassinated Talaat Pasha, the former Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire, in Berlin on March 15, 1921—in a ceremony on April 21, 2017.

Marseille Mayor Jean-Claude Gaudin, along with several French public and political figures, as well as representatives of the French Armenian community came together to officially welcome the naming of the square.

The inauguration event was organized jointly by the Marseille municipality and the Coordination Council of Armenian Organizations in France (CCAF).

Soghomon Tehlirian Bio, Education, Ideology

Tehlirian was born in the village of Nerkin Bagarich, in the Erzurum region, and grew up in nearby Erzincan (Yerznga).

He began his education at an Evangelical school in Erzincan, then attended the Ketronakan School of Constantinople. He began his higher education in engineering at a German university but returned to Erzincan when the First World War broke out.

In June 1915, during the deportation of Erzincan Armenians, Tehlirian witnessed the murder of his mother and brother, along with the rape and murder of his three sisters. He was struck on the head and left for dead.

He survived and escaped to Tiflis, where he joined the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF). He participated in volunteer units commanded by General Andranik and also took part in the Volunteer regiment commanded by Sebouh.

In 1921 he was assigned to the ARF’s Operation Nemesis, which sought to punish Turkish officials guilty of organizing and carrying out the Armenian Genocide.

Tehlirian’s main target was Talaat Pasha, one of the triumvirate of Young Turk leaders who had ruled in the last days of the Ottoman Empire; he was a former minister of the interior and a grand vizier (prime minister).

Talaat was killed by Tehlirian with a single bullet on the morning of March 15, 1921, in Berlin, in broad daylight. Tehlirian did not flee the scene and was immediately arrested. He was tried for murder but was exonerated by the German court.

His trial became a highly sensational event, examining not only Tehlirian’s guilt but also that of Talaat Pasha for the Armenian deportations and mass killings. The trial influenced Polish lawyer Raphael Lemkin, who was later to coin the term “genocide.”

He reflected on the trial, “Why is a man punished when he kills another man? Why is the killing of a million a lesser crime than the killing of a single individual?” After the assassination, Tehlirian moved to Serbia and married Anahit Tatikian, who was also from Erzincan.

The couple moved to Belgium and lived there until 1945 when they moved to San Francisco. Tehlirian died in 1960 and is buried at the Ararat Cemetery in Fresno, California.

“I have killed a man. But I am not a murderer.”

Soghomon Tehlirian assassinated Mehmet Talaat Pasha, the architect of the Armenian Genocide. After the assassination in Berlin, Tehlirian was captured, tried in a German court, found not guilty, and released.

He was born in Nerkin Bagarich in the Ottoman Empire. Although he lived abroad for several years, he returned to fight in the Armenian volunteer battalions in the Caucasus. At that time, many of his family members were deported and killed.

Tehlirian was witness to some of these deaths and according to his memoirs, 85 of his family members perished. Following the end of World War I, the organizers of the Genocide, including Talaat, were tried by a tribunal and condemned to death in absentia.

By that time, they had dispersed to different parts of the world and they could not be subject to the court’s judgment.

Insistent that the martyrs of the Genocide must be avenged, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation organized a plan, called “Operation Nemesis” orchestrated by Shahan Natalie.

Tehlirian was assigned the duty of killing Talaat in Berlin and on March 15, 1921 he completed the task. Tehlirian was immediately captured and stood trial in Berlin. The short trial was followed by an hour-long deliberation by the jury, which concluded with a “not guilty” verdict.

He moved to Serbia and then to the United States, where he died. He is buried in Fresno, California, his grave adorned by an obelisk atop which rests a bronze eagle clutching a snake with its talons.

Interesting fact Rafael Lemkin, the Polish lawyer who invented the word “Genocide,” followed Tehlirian’s trial and was inspired by the proceedings to ask: “Why is a man punished when he kills another man? Why is the killing of a million a lesser crime than the killing of a single individual?”

The Trial of Soghomon Tehlirian (full transcript)

The Case of Soghomon Tehlirian Armenian Political Trials Translated by Vartkes Yeghiayan Grade Level: Eleventh Grade to Adult Soghomon Tehlirian, a survivor of the Armenian Genocide, assassinated Talaat Pasha in Berlin in 1921.

This work presents the case in detail. Talaat, Minister of the Interior and mastermind of the Genocide, had fled Turkey to seek refuge in Germany where he continued to labor for Pan-Turkism.

He had been tried in absentia by the Turkish authorities and sentenced to death for the atrocities he planned and carried out, but no official effort had been made to apprehend him and bring him to justice.

After Talaat’s assassination in Berlin, Soghomon Tehlirian, who admitted to committing the murder, was given a jury trial.

During the two-day trial, expert witnesses and eye-witnesses testified not only about the murder itself but about the details of the Armenian Genocide and Tehlirian’s physical and mental condition as the only survivor in his family.

The jury acquitted Tehlirian of the crime. He eventually moved to the United States and lived out his years in San Francisco.

Talaat Pasha assassination

Talaat Pasha was assassinated in Berlin on March 15, 1921. He was one of the three officials heading the Young Turks in the dying days of the Ottoman Empire and the chief organizer of the Armenian Genocide. He fled to Berlin as the Allies moved towards victory in the First World War.

The military tribunals that took place in occupied Constantinople in the years 1919 and 1920 sentenced him and other former high officials to death in absentia for their roles in the horrific crimes committed particularly against the Armenians and other Ottoman Christian subjects.

However, those sentences could not be carried out by those courts, and, quite soon, the revolutionary movement led by Mustafa Kemal overtook the proceedings.

Western powers subsequently came to their own agreements with the new Turkish government, now based in Ankara. The Armenians, however, did not allow those verdicts to fall by the wayside.

What is referred to as “Operation Nemesis” oversaw the pursuit and killing of a number of senior officials who were instrumental in carrying out the Armenian Genocide.

Perhaps the most far-reaching of those assassinations – certainly the most sensational – was that of Talaat Pasha, who was killed in broad daylight in Berlin, on March 15, 1921. Soghomon Tehlirian was the one who pulled the trigger.

Like many of his compatriots, he had witnessed the horrors of 1915, watching his family massacred before his eyes, he himself being left for dead.

Surviving, and joining the ranks of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, Tehlirian gained some fighting experience and training before being involved in the covert assassination plots.

He arrived in Germany, took up lodgings right by where Talaat Pasha was residing in Berlin, and, after some investigations, carried out his mission. Part of the point was to get caught, have a trial, and generate coverage for it.

The whole affair was a major event for its time, not merely because it brought to light the realities of the Armenian Genocide that were slowly but surely being shoved aside, in particular in Germany itself, where news of such massacres in an allied country had not been freely spread during the war, but because, in the end, Soghomon Tehlirian was acquitted for his crime. There was no denial, no question of who killed whom and how.

But, after being exposed to the whole story the transcript runs for pages and pages, detailing Tehlirian’s horrific experiences and later mental state the jury thought it best to let Tehlirian go.

Needless to say, the case caused an immense outcry and provided a strong sense of vindication for Armenians already dispersed around the world. Tehlirian later lived in Serbia, before finally moving to California, where he died in 1960.

He is buried in Fresno, at the Ararat Cemetery, underneath an obelisk capped by an eagle with outstretched wings attacking a snake. Talaat Pasha’s remains were moved from Nazi Germany to Istanbul in 1943 and buried with full honors at a national monument that still stands.

Armenian Political Trials Translated by Vartkes Yeghiayan

Soghomon Tehlirian, a survivor of the Armenian Genocide, assassinated Talaat Pasha in Berlin in 1921. This work presents the case in detail. Talaat, Minister of the Interior and mastermind of the Genocide, had fled Turkey to seek refuge in Germany where he continued to labor for Pan-Turkism.

He had been tried in absentia by the Turkish authorities and sentenced to death for the atrocities he planned and carried out, but no official effort had been made to apprehend him and bring him to justice.

After Talaat’s assassination in Berlin, Soghomon Tehlirian, who admitted to committing the murder, was given a jury trial.

During the two-day trial, expert witnesses and eye-witnesses testified not only about the murder itself but about the details of the Armenian Genocide and Tehlirian’s physical and mental condition as the only survivor in his family.

The jury acquitted Tehlirian of the crime. He eventually moved to the United States and lived out his years in San Francisco. The trial examined not only Tehlirian’s actions but also Tehlirian’s conviction that Talât was the main author of the Armenian deportation and mass killings.

The defense attorneys made no attempt to deny the fact that Tehlirian had killed a man, and instead focused on the influence of the Armenian Genocide on Tehlirian’s mental state.

Tehlirian claimed during the trial that he had been present in Erzincan in 1915 and had been deported along with his family and personally witnessed their murder. When asked by the judge if he felt any sort of guilt, Tehlirian remarked, “I do not consider myself guilty because my conscience is clear…I have killed a man. But I am not a murderer.”

Operation Nemesis: The Assassination Plot to Avenge the Armenian Genocide by Eric Bogosian

One morning in March 1921 a large man in an overcoat left his house in Charlottenburg, Berlin, to take a walk in the Tiergarten. A young man crossed his path, drew a pistol, and shot him in the neck.

Emitting a groan ‘like a branch falling off a tree, he fell dead. The assassin ran but was arrested by the crowd. ‘What do you want?’ he asked. ‘I am Armenian, he is Turkish. What is it to you?’

The victim was Talat Pasha, erstwhile interior minister of the Ottoman empire and convicted war criminal. His nemesis was Soghoman Tehlirian, an engineering student and agent of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation.

Talat topped the ARF’s list of targets: revenge for the genocide of some 1.5 million Armenians between 1915 and 1917. Like Israel’s abduction and trial of Adolf Eichmann, the ARF mixed vengeance with the ‘propaganda of the deed’.

To serve justice, the victims broke the law. The ensuing trial would enter the historical record; the sentence would be the world’s memory.

Tehlirian was a Dostoevskian martyr: epileptic, chastely passionate about his girlfriend, the beautiful Anahid, haunted by nightmares of his decapitated mother, and devoted to killing.

Serving in a Russian-trained Armenian unit, he had witnessed the aftermath of the genocide and learned that his mother and brothers had been murdered, and his sisters raped.

After the war, he assassinated an Armenian traitor in Constantinople on his own initiative. In early 1919, the ARF recruited him and sent him to Watertown, Massachusetts, where Armenian Americans were funding and planning their revenge.

They told him not to flee after shooting Talat and primed him for his trial. In court, Tehlirian perjured himself, to save his life, protect the conspiracy and publicize the genocide. He testified that he had witnessed his family’s murders, and had escaped from a pile of corpses.

Although he had worked with a team, he claimed to have acted alone, after encountering Talat by chance. The judge did not ask how Tehlirian had entered Germany on a Persian passport, bearing a Swiss student visa and a large amount of money.

Perhaps Germany, as Turkey’s ally, had been complicit in the genocide. Aubrey Herbert, Evelyn Waugh’s father-in-law, and the inspiration for Sandy Arbuthnot in John Buchan’s Greenmantle may have informed the ARF where Talat was hiding.